By this point in the Divine Innovation journey it should hopefully be clear that the founding myths undergirding Silicon Valley are slippery, ahistorical, and harmful. They laud meritocracy and Soylent-sipping Allbirds-sporting libertarian-eugenic self-optimizing.

The lone tech genius is divorced from the economic and racial systems that make him a plausible archetype. He and his contemporaries shape the technologies that we use on an everyday basis, even if (1) we despise who they are and what they believe, and (2) they doppelgäng Rasputin à la Twitter founder and CEO Jack Dorsey:

Spooky!

The same myths circulated within the tech world and beyond also shape perceptions of apocalypse: what is regarded as the end of this world and what doesn’t get the same consideration.

Somewhere amidst the doomscrolling and before my bajillionth hour on Zoom this spring, I remembered how Ruth Hopkins, a Dakota/Lakota Sioux writer and enrolled member of the Sisseton Wahpeton Sioux Tribe, related an experience at the gym several years back.

Apocalypse has happened, and has been happening, in the United States for centuries. And as previously described in Divine Innovation, settler-colonial technologies have been an enduring cornerstone in an apocalyptic, consciously world-ending project in the name of Christendom and white, Protestant “civilization.”

Founding myths, and the violence with which their belief systems are policed as truth, obfuscate the reality of the long apocalypse. It’s no small task to use these same technologies to reveal the farce behind the myth.

A stroll through the history of cinema—ah yes, that screen of yore—can illuminate the struggle of using modern technologies to fight the founding myths that settler-colonial technologies circulate.

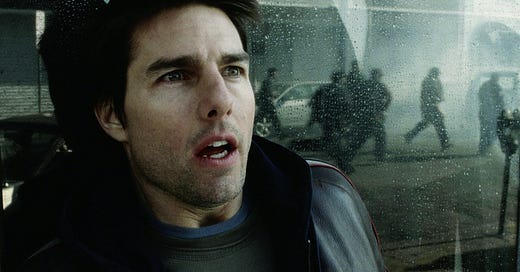

Let’s take War of the Worlds, the 2005 film. Here’s a trailer if you’ve somehow forgotten about this Spielberg-produced, Tom Cruise-saturated blockbuster; how dare you.

The central plot has existed in various media since its original publication in book form in 1897. Resource-starved Martians invade Earth, wreak havoc through terrifying tripod-machines, and nourish themselves with human blood. Spoilers, but: in the denouement, Earth’s pathogens passively kill off the Martians. Humanity, shaken, survives.

H.G. Wells, the famed English writer, penned the novel as allegory. The War of the Worlds’ central concerns came from a humbly earthly and human walk with Wells’ brother Frank. Wells recalled the book’s genesis as follows:

“Suppose some beings from another planet were to drop out of the sky suddenly,” said [Frank], “and begin laying about them here!” Perhaps we had been talking of the discovery of Tasmania by the Europeans – a very frightful disaster for the native Tasmanians! I forget. But that was the point of departure.

That mass extermination can be summed up so placidly in the words “discovery” and “very frightful disaster” is less a slippage than it is a symbol of a larger trend. Even as Wells musters some degree of sympathy for an Indigenous nation confronted with the sudden and violent invasion of the land- and commodity-hungry British Empire, he concludes that his audience can best appreciate that perspective shift through otherworldly and decidedly non-human terms. Transmuting the invaders into monster form was what made Wells’ white readers able to think about the humanity of anyone else except for themselves—obliquely, implicitly, and fleetingly at that.

The 2005 film’s dull apolitical repackaging is thus less of a dramatic departure from its written predecessor that it may seem upon first glance. Spielberg’s Boston-based adaptation is certainly devoid of any gesture to the story’s original, colonial undertones; Plymouth Rock mere miles away, a missed opportunity for sure, but the original was also couched in metaphor to comfort the viewer/reader.

Yet if anything, the version of the plot best known for causing a popular upheaval was its 1938 rendition, a radio broadcast narrated by Orson Welles. It’s become a fixture in US popular history as a milestone of technological development. “Common knowledge” recalls how listeners tuning into the program midway through believed in all sincerity that Martians had arrived on Planet Earth to exterminate its inhabitants.

Contemporary research—most notably Broadcast Hysteria: Orson Welles's War of the Worlds and the Art of Fake News—dismisses this tall tale. The program did not sow mass panic. Public broadcasting statistics from the time suggest that less than two percent of US households listened to the program at all; most were tuned in to The Chase and Sanborn Hour, a comedy show by ventriloquist Edgar Bergen. Why do we remember Welles’ broadcast as a terrifying chapter in US history, then, while Bergen and his show are met present day with a “huh?”

The immediate fallout from the program was miniscule. But as the subtitle of the book above may suggest, the media sensationalized the broadcast (for profit) after the fact. Here’s the cover of New York’s very own Daily News from the next morning:

The rumor spread from that headline and similar ones. Professors of Communication Jefferson Pooley and Michael J. Socolow elaborate:

From these initial newspaper items on Oct. 31, 1938, the apocryphal apocalypse only grew in the retelling. A curious (but predictable) phenomenon occurred: As the show receded in time and became more infamous, more and more people claimed to have heard it. As weeks, months, and years passed, the audience’s size swelled to such an extent that you might actually believe most of America was tuned to CBS that night.

With decreasing recognition of colonialism as the original impetus for The War of the Worlds, so arose this quaint, queer story of pre-Internet trolling and misinformation. This narrative of prank-by-radio turned Orson Welles into a household name, his ascendance brought about by the media’s own mythmaking. The radio story served as a whitewashing of a whitewashing; the transgressor became sneaky, sneaky Orson, rather than empires and world-destroyers in tripod form. The story’s victims changed too, now gullible listeners rather than subjects of Martian/British violence.

Even a tale of apocalypse can be watered-down, co-opted, commercialized, turned anew into myth. Our jaunt through the cinema-verse and associated media thus directs us to ask, who benefits from prophesying the end of the world through these technologies? How does that information circulate within new and existing distributional systems? What truths shine through, and what falsehoods proliferate? How will apocalypse be remembered and forgotten if we survive? Who will survive?

These questions sound with increasing volume as we approach a confluence of horrifying seasons: holiday, Scorpio, election, flu. It’s a combination with apocalyptic potential. At least some part of that world’s end is nigh.

The kinds of tools that inspired Wells’ oeuvre, ones that destroyed existing worlds as they proliferated others, still exist. Silicon Valley shares its source code with those technologies. In the tech world’s hands are tools to summon apocalypse, to be sure, as well as ones that broadcast and interpret it.

There are potent forms of apocalypse to prepare for. An armed, alt-right insurrection—an even larger one—may be hours away. The coronavirus pandemic is spiking once more. Ecological disasters are growing in number and power.

Precedent suggests that the tech industry will do what it can to survive these onslaughts at the expense of everyone else. Its playbook encourages denial, slippery allegiances with oppressive powers, profiting from disaster, and, when all else fails, colonizing space.

The lone tech genius and his apostles have an active interest in making current forms of accelerated societal collapse the new normal. If their wares can make them a buck, so be it, say their ethics.

They see salvific potential in their own (divine) innovation, even as their practices are divorced from the utopian beliefs and rhetoric that they market. And their platforms, designed for doomscrolling, splinter interconnected crises into separate issues, and maximize anxiety and engagement in the name of revenue.

This issue would be remiss (if not delusional) to conclude on a positive note. But connecting various forms of apocalypse and unseating the founding myths that bolster them is far more than a palliative exercise. It can challenge efforts to profit off apocalypse, and confront the material and ontological power of the technologies that sustain current entropy. As the tech world prepares for blast-off, everyone else can throw them off orbit.

“The past is ours only in so far as we have it present; and the future is ours only in so far as we have it already present,” preached theologian Paul Tillich. “We possess the past by memory, and the future by anticipation.”

Divine Innovation covers the spiritual world of technology and those who shape it. Published once every three weeks, it’s written by Adam Willems and edited by Vanessa Rae Haughton. Find the full archive here.