[7.0] Is polling a prophecy?

“Dismantling the Nate Silver-industrial complex” should be on your bucket list

Divine Innovation covers the spiritual world of technology and those who shape it. Published once every three weeks, it’s written by Adam Willems and edited by Vanessa Rae Haughton. Find the full archive here.

Writing this on October 2, I’m unaware (more than base-level) of what the world will look like when this issue whooshes into your inbox on October 11.

The current source of anxiety this week is: will the United States have a new POTUS, or the same one? With a runny nose, or in the ICU?

The time between my drafting and your perusal of this issue will probably have more than its fair share of shocking headlines. Divine Innovation does not pride itself in fortune telling, nor will it try to.

At least where the US presidency is concerned, uncertainty is a feature of the system, not a bug. Presidential assassinations and deaths in office speak to this truth. Sudden episodes that can drastically rechart a country’s political direction and outlook; a president leaving office far earlier and differently than the public had envisioned.

But the history of the path to the White House, how a president enters the Oval Office, too, is replete with stories of unexpected developments and outcomes.

Take the iconic “DEWEY DEFEATS TRUMAN” headline. The Chicago Daily Tribune took presidential polling data at its word. (It worshipped it? Idk.) On the night of the 1948 presidential elections, as members of the newspaper’s masthead slumbered, they felt assured that the morning edition would reflect fact, not farce. Polling was their lullaby, and ultimately an infamous embarrassment.

And then there’s, err, this:

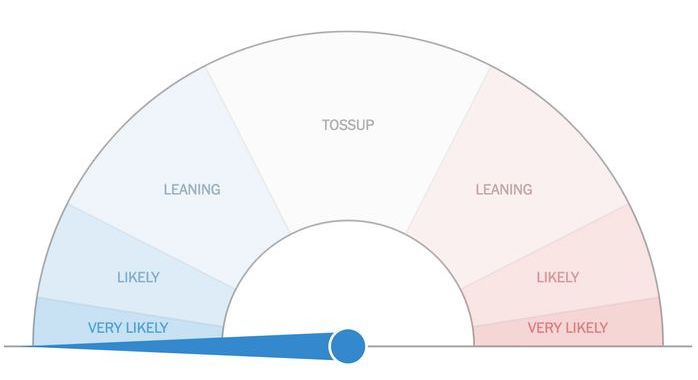

Not sure if you’ve heard, but this ended up not being the result?? And many people ended up shocked, the New York Times and other outlets (*ahem*, Nate Silver’s FiveThirtyEight) forced to backpedal and rationalize an outcome that their forecasts did not favor.

Both analog forms of polling in 1948 and glitzy ~*big data*~ election models in present times can mess up. It’s easy to blame the numbers or to wag our fingers at the outlets that tabulate and circulate them. But as with most things algorithm, the issue is not with the polling and modelling per se, but with the people crunching them, and the assumptions they make in the process.

It might be worth going back to the pre-DJT administration era to think about polling, and to consider what this industry actually has to offer the body politic.

Numbers, crunching

The fruit, it is low hanging in the spiritual world of technology.

Thank you David Rothschild and Neil Malhotra for smacking a nice, full-circle, spiritual title onto your research:

Are public opinion polls self-fulfilling prophecies? Can public opinion itself influence public opinion? Rothschild and Malhotra elaborate:

Before asking people about their opinions on three contemporary public policy issues—withdrawing troops from Afghanistan, free trade agreements and public financing of elections—we randomly assigned respondents to receive aggregated polling information showing support for the public policies ranging from 20 percent to 80 percent. Averaging across the three issues, we found that moving public support across the range increased support for the policies by over eight percentage points. In other words, people were more likely to support the policy initiatives if they were told that they had more support in the general public.

When the researchers showed fictitious, increasingly favorable public opinion polling, the subjects’ opinions on free trade improved by 13.5 points, on withdrawing US forces from Afghanistan by 6.3 points, and on public financing of elections by 3.5 points.

In other words, according to this study, public opinion begets public opinion. This finding aligns with the foundational public opinion research done by Herbert A. Simon in 1954 on what he called the “bandwagon effect.” Declaring an opinion a social trend with some oomph behind it makes the same trend even more powerful. The polling entrenches reality. It renders the bandwagon’s vision an invariable and inevitable future.

Before running away with this research as a prophecy on prophecy, so to speak, it’s critical to look at the conditions and questions Rothschild and Malhotra add to their analysis. For one, they predict that highly politicized social issues are less swayable. This explains the varying changes to public opinion in their study, where people are more likely to change their opinions on free trade than they are on forever wars abroad. But they have questions:

How does this effect differ between public policy questions and elections? At minimum, most elections are partisan, by definition, but they can vary in the extent to which voters are ambivalent and possess information. More generally, what type of information about collective opinion is most impactful and why? What is the mechanism underlying the results: desire to be part of the winning team or the rational processing of signals about the quality of public policies? Which types of people are most susceptible to learning about public opinion through polling information?

What is it about polling that can imbue it with prophetic power? Does it have this same power in all political arenas, albeit to differing degrees? And if polling’s bandwagon effect seems so determined, why didn’t the bandwagon’s prophecy come true in 2016?

Your prophecy’s showing

In his introduction to the Penguin Classics edition of The Life of Milarepa, scholar Donald S. Lopez discusses the place of prophecy in Buddhism:

Prophecies are important elements of Buddhist literature… in the sutras and legends (avadā̄na), the Buddha will often make a prophecy or prediction, usually of the future enlightenment of a member of his audience. Scholars find a different meaning in the Buddha’s prophecies, using them to date Buddhist texts. Therefore, if the Buddha makes a prophecy about the emperor Aśoka, this is proof that the text was composed after Aśoka… That is, prophecy is regarded as a device by which Buddhist authors project present importance into the past, enhancing that importance by expressing it in the form of a prophecy by the Buddha himself.

Lopez’s argument injects the human into the equation. For millennia, people have couched their own political concerns in the form of prophecy, ascribing their opinions to authoritative spiritual sources like the Buddha to add weight to their claims. Lopez describes prophecies that concern Ashoka, an Indian emperor from the third century BCE. A simplistic take would suggest that what was ascribed to the Buddha “then” is bolstered by “big data” now; it’s a bad hot take, though, in that it relegates Buddhist traditions to the past (which they certainly are not), and pits data and Buddha as mutually-exclusive realms of authority.

Instead, scholarly approaches reveal the particular, historically-specific anxieties that underlie even the most stoic prophecies. Rothschild and Malhotra question the relationship between free trade, the US occupation of Afghanistan, and elections to the force of political prophecy; they do so because those are topics that matter to them and to a 21st century US electorate. Whether or not polling can sway elections is a question of serious concern, even if it’s dressed in academic garb and reveals itself behind a research journal’s paywall. If polling alone can swing an election, what is honest or resilient about our current democratic norms?

At that question’s impasse—an especially fitting one in the weeks before the election—we can begin to work towards an answer by remembering how prophecy passes through us. What happens once we receive a prophecy? What happens next?

Longtime readers of Divine Innovation might have foreseen (ha!) this throwback to Issue 2.0, to the question of how our approaches to prophecy determine the outcome. In How to Write an Autobiographical Novel, writer Alexander Chee describes his evolving relationship to tarot cards. He learned to approach tarot cards as something more dynamic and potential than an unwavering description of the yet-to-come:

“[They] show me the possibilities of the present,” he writes, “not the certainties of the future.”

What would it mean to approach political polling in this way: to take its numbers and hot takes as not certainty, but possibility? A predicted outcome that requires active contribution to reach its goal, rather than passive expectation and acceptance?

For one, this reframing would push us to inspect the innards of the prophecies we’re told, to question the assumptions that undergird them. That FiveThirtyEight’s election models are grounded in a good-faith political worldview, in which every vote cast will be counted and respected, speaks to a powerful, lackadaisical, contemporary approach to prophecy. Last time I checked, the website gives Biden an 85% chance of winning the 2020 election. But FiveThirtyEight founder Nate Silver’s worldview, a vision that structures his team’s influential forecasts, should ring all the alarm bells in our cortexes. My synapses shrieked when I read his pontifications:

We assume that there are reasonable efforts to allow eligible citizens to vote and to count all legal ballots, and that electors are awarded to the popular-vote winner in each state. The model also does not account for the possibility of extraconstitutional shenanigans by Trump or by anyone else, such as trying to prevent mail ballots from being counted.

A Chee-esque response to this bold assumption—to not even begin to bash the “shenanigan” phrasing, omg—would turn information into action. Translating FiveThirtyEight’s prophecy would necessitate organizing against voter disenfranchisement; an unconditional commitment to respond to antidemocratic outcomes of the election; and shunning any belief in politics as a sport between opposing teams, one hospitable to odds and forecasts, rather than a powerful mechanism that rewards some and punishes others. It requires active, collective participation in the political process beyond casting a vote.

But it would also encourage us to find better prophecies. To reject the kind of short-sighted, shoulders-back cockiness that defines the “optimized” political prophecies churned out of the tech industry and its tentacles. To instead endorse and invest in prophecies related lucidly to the present, tied hopefully and realistically to shared and actionable futures.

Critical race and digital studies scholar Ruha Benjamin writes, “The uncertainty, I think, is what we make of it.” We’re on the cusp of something. Prediction needles can point in any direction. The real battle over the prophecy’s realization takes place in every other arena. You’re already here for it.

P.S.

If you have the time (I hope you do!), here are a few groups that are already building towards less terrifying election outcomes, creating different prophecies. It’s not too late to help out (and political engagement is more than a single election anyway):

This “No Regrets” guide to the election offers a banquet of ideas, and is a great place to start (link)

Power the Polls is addressing the poll worker shortage brought on by the pandemic (link)

SURJ is organizing against a contested election, and wants to swing Georgia left (link)

5Calls applies pressure to the politicians already in office, and provides scripts and instructions for its extensive list of burning issues (link)

Check out Southerners on New Ground (link)

The comments section is a thing also, where you can share other movements and organizations you want others to know about. Be blessed!