The #inspo for this series on cakes came from (get this) a documentary on Hulu. Yes, I, a plebe hoping to see ganache with panache, successfully wrangled Hulu’s atrocious, sticky interface to view Ottolenghi and the Cakes of Versailles:

Israeli vegetarian chef Yotam Ottolenghi’s eponymous œuvre smacks of pandemic-escapism; skewing, frankly, closer to Selling Sunset than Jiro Dreams of Sushi. OatCoV details how Ottolenghi assembled a crack shot squad of dessert prodigies to resurrect 18th century Versailles’ cake culture for a one-night-only dinner gala, serving food and joy to a demographic in need: the most loyal benefactors to NYC’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Tbh, the documentary made me somewhat queasy. Filmed in the summer before Covid’s eruption, Cakes of Versailles is unintentionally oracular in what it foretells, highlights, and casts aside.

Foreshadowing oligarch superspreader events, for one, sure.

But more importantly, as the film historicizes the decadent details of the “golden age” of Versailles—cakes upon cakes, Maries-Antoinette, kickass topiaries—and its eventual collapse, the diachronic dots remain unconnected, as though let-them-eat-cake-esque paternalism were a ghoulish philanthropy relegated to the past.

Ottolenghi further discusses the “modern technological processes” that brought cake into the world, like the industrialization of refined sugar, but not once does he note the white supremacist social developments that made such sugar a possibility: genocidal European colonialism and chattel slavery in the West Indies. With these brutal specters and their continued presence unnamed, OatCoV gestures unawares to the hubris and unrepaired histories functioning as preconditions for this “apolitical” cakey display at the Met. A harbinger of the grossly unequal societal collapse underway but unacknowledged and further fueled via virus.

If cake is canon, then sugar is its genesis.

Refined sugar was a truly “disruptive” technology at the time of its commodification in the 1600s. In kitchens, our dessert palette underwent a sweet transfiguration. Where people once consumed “sweets” more akin to the mealy, floury taste of pasta, they now ate sugary, jiggly jellies, cream-filled pastries, and pyramids of cake.

Cakes were part of the French royal court’s symbolic and diplomatic efforts. As Cakes of Versailles elaborates, the French used sugar to fatten their coffers and showcase the kingdom’s might. With manicured gardens as the other half of this one-two punch, Versailles hoped to flaunt French mastery of nature and their “advanced” civilizational practices. The court’s banquets boasted of the gardens’ fecundity by placing fruits and other foodstuffs in pyramids; mimicking, in unabashedly Orientalist fashion, how spices are presented in the ~*Souks of the Orient*~. The cakes proved industrialized prowess and the voraciousness with which the monarchy could consume valuable sugar.

In this sense, food itself was a literal technology of the state. It convinced diplomats of French might and longevity; a nation to be reckoned with, sure, but also one to ally with. Garner an invitation to sit at the French table. Bon appétit!

“Versailles was kind of the equivalent to Disneyland,” Ottolenghi muses in the documentary. To me, that reference paints Versailles as the worst of the economic and social mores of its time, all packaged glibly as entertainment. To our chef-documentarian, it means Versailles was a destination open to the public, which permitted French citizens and foreign dignitaries alike to witness its grandeur. But this decadence invited its decline. “Commoners” saw how wasteful their rulers were, juxtaposing peasant paucity with elite plenty. This, along with other variables, catalyzed unrest culminating in the French revolution, guillotines wheeled out to off the royals’ heads.

The history of these ironies is recounted quasi-diligently in Cakes of Versailles. The film acknowledges Versailles’ collapse via gluttonous splendor. It’s therefore extra-informative that the film channels its inner Frenchman—ignoring French colonial history, that is—by overlooking the brutality behind the sugar supply chain. Like, where does Ottolenghi think all this refined sugar came from?

Slavery is a destructive, brutal practice at the same time it is world building. It constructs new forms of social and economic relations through subjugation. In the West Indies, the confluence of sugar plantations and the enslavement of West African people created a unique historical process, argues CLR James in The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L’Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution:

Wherever the sugar plantation and slavery existed, they imposed a pattern. It is an original pattern, not European, not African, not a part of the American main, not native in any conceivable sense of that word, but West Indian, sui generis, with no parallel anywhere else.

Placing James in conversation with historians Trevor Burnard and John Garrigus, co-authors of The Plantation Machine: Atlantic Capitalism in French Saint-Domingue and British Jamaica, can help us grasp the larger chronology of this system. “The Caribbean was the first area in the New World to experience European imperialism and was battered by those forces for longer than anywhere else,” the historian duo writes. Europeans’s first act was genocide; they eliminated the Indigenous people of the region, the Taíno. They further destroyed the area’s ecosystem, razing it of its hardwood forests. From there, “they imposed a nightmarish system of slave labor to work this new land.”

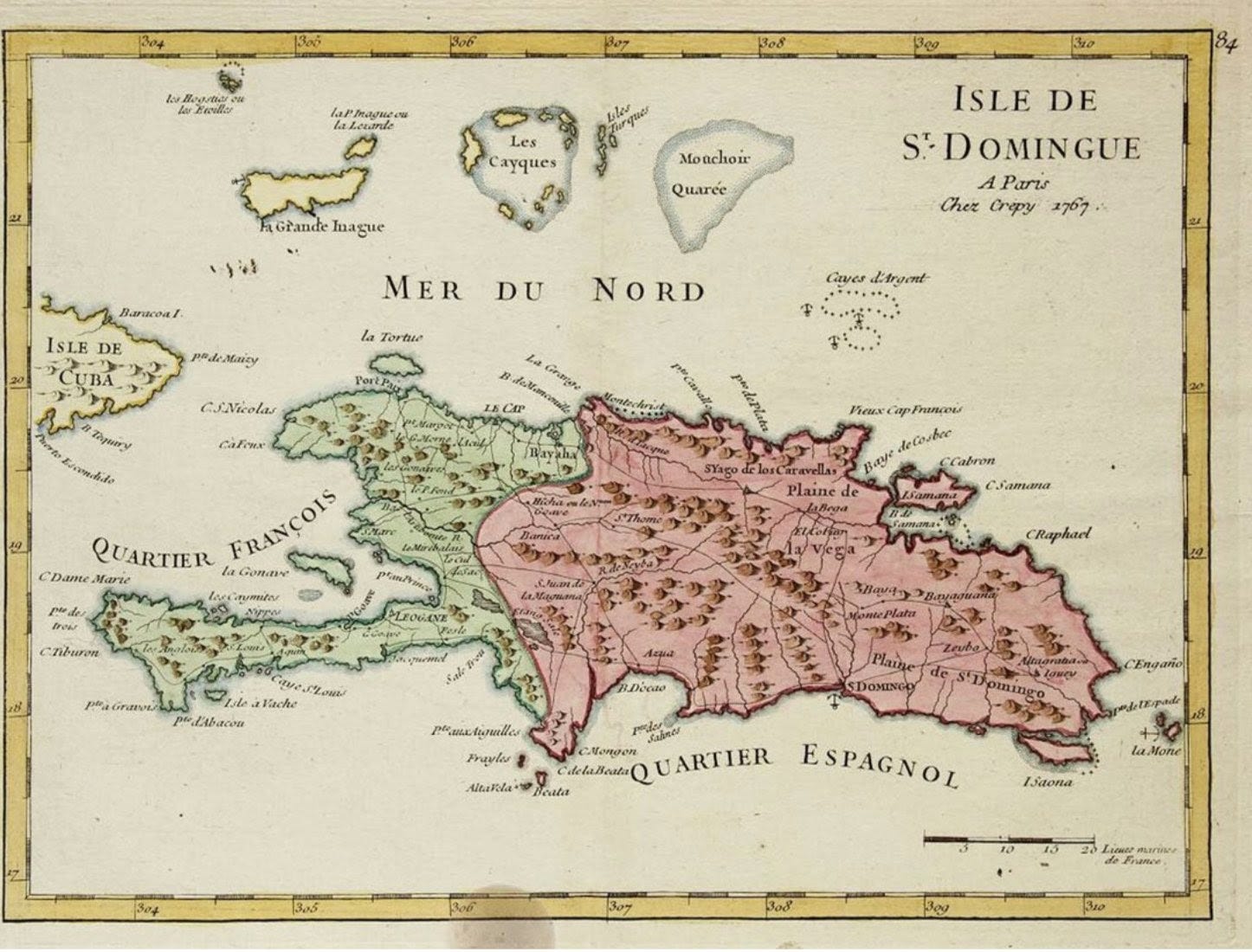

The French controlled Saint-Domingue—what is present-day Haiti—by the middle of the 17th century, and, from there, established a sugar plantation system built on slave labor. People enslaved in the colony were forced to work twelve-hour days under literally tortuous conditions. French colonizers consistently “imported” West African people abducted into slavery to make up for the high number of deaths. Beyond survival, pregnancy and having children were almost impossible because of the abuse: physical, labor, and lack of proper nourishment.

Not done yet, the French then structured a grifty, almost MLM-ish economic system to maximize profit for the metropole. Writes James:

Whatever manufactured goods the colonists needed they were compelled to buy from France. They could sell their produce only to France. The goods were to be transported only in French ships. Even the raw sugar produced in the colonies was to be refined in the mother-country, and the French imposed heavy duties on refined sugar of colonial origin.

Ottolenghi, then, was partially right if he thought sugar was from France itself, as its final transfiguration into a finer, purer form took place in industrial coastal towns. The empire kept Saint-Domingue’s profits and industrial capacities low through a chimera of protectionist policies, all of which benefited the economic development of the mainland.

The French established a distinctly modern commodity chain wrapped up in other modern processes, James argues:

The sugar plantation has been the most civilizing as well as the most demoralizing influence in West Indian development. When three centuries ago the slaves came to the West Indies, they entered directly into the large-scale agriculture of the sugar plantation, which was a modern system. It further required that the slaves live together in a social relation far closer than any proletariat of the time. The cane when reaped had to be rapidly transported to what was factory production. The product was shipped abroad for sale. Even the cloth the slaves wore and the food they ate was imported… from the very start [they] lived a life that was in its essence a modern life. That is their history – as far as I have been able to discover, a unique history.

Burnard and Garrigus posit that eighteenth-century capitalism could not exist without this system. Or the racial capitalism we have today, for that matter. The plantation’s new “integrated” form was a primary driver behind many systemic changes. By “integrated” the historians mean a plantation that both grew sugarcane and transformed it into sugar crystals (not fully refined) through manufacturing. Through a somewhat vertical supply chain, sugar plantation owners and colonist thinkers began to imagine their properties as machines. Antigua’s Samuel Martin in his 1765 Essay upon Plantership envisaged the following:

A plantation ought to be considered as a well-constructed machine, compounded of various wheels, turning different ways, and yet all contributing to the great end proposed; but if any one part runs too fast or too slow in proportion to the rest, the main purpose is defeated.

If the sugarcane was harvested too long before it entered the manufacturing process of crystallization, for instance, then “the machine” collapsed upon itself. Meanwhile, if this same metaphorical “machine” featured a larger and more experienced workforce, then it could produce a semi-refined white sugar that was twice as profitable as brown sugar. “It was in these Greater Antilles colonies that the full economic, social, and cultural impact of this mode of sugar planting was expressed,” Burnard and Garrigus conclude, suggesting that, beyond harnessing the power of metaphor, the slaveowner-industrialists of sugar plantations created work orders of scientific discipline that hinged upon violent discipline.

Their system further treated enslaved people as machines. As both a “thing” with “life” to it, that is, and as property. The historians continue:

Sugar planters’ attitude that their enslaved workers were flexible and expendable capital investments was consistent with an emerging industrial mentality. Planters’ skillful and increasingly flexible deployment of “human resources” (to give a modern term to this emerging way of seeing people in capital investment terms) demonstrated their place on the cutting edge of financial and industrial capitalism.

Crucially, Burnard and Garrigus chart the use of race as technology. During the Seven Years’ War between the French and British, some French colonists switched sides knowing the Union Jack ensured access to North American markets previously inaccessible to French mercantilists. With a liberalized economy a more tantalizing reward than national allegiance, many of Saint-Domingue’s élites traded allegiances.

“Versailles doubted that Saint-Domingue’s planters were as committed to the empire as they were to their commercial ambitions” Burnard and Garrigus note. The French state was desperate to maintain loyalty to nation over economy; it did so by formalizing extant racial prejudices. Thus, this before-and-after:

Before the Seven Years’ War, a literate, nominally Christian man or woman who had freedom, wealth, and connections to a prominent colonial family was considered a member of the colonial elite. By the 1760s and 1770s, however, both societies came to embrace the idea that “whiteness” was more important than mere freedom, or even wealth, in determining social and political position.

This did not mark the “invention” of anti-Black racism and white supremacy as much as the political taxonomization of a hierarchy. Such a system continues to rear its head. In Pure America: Eugenics and the Making of Modern America, public historian Elizabeth Catte notes that Virginia only made reporting one’s race optional for marriage certificates in 2019. It removed “octaroon” and “teutonic” as possible racial categories at the same time. Eugenic leisure activities beyond marriage licenses—23andMe DNA tests come to mind here—continue to reward approaching ethnicity and race as fractions.

Saint-Domingue was clearly the origin point for much more than Versailles’ Great A-cake-ening. Its history elucidates beyond this Ottolenghi rebuttal. The colony, at the forefront of political and economic changes—an environment in which industry was more powerful than nation, where people were both living and property—demonstrated what kinds of shifting social relations were to come; proletarian working conditions and growing national power through state-enforced racism in the face of globalization.

By the eve of the Haitian Revolution led by Toussaint Louverture (above), Saint-Domingue was coveted as the most profitable colonized territory on earth. Yet, at the same time that the French invested so heavily in the colony to keep its house-of-cards economic engine going, it also contributed to its own downfall by sowing the conditions for revolt. Writes CLR James:

The slaves worked on the land, and, like revolutionary peasants everywhere, they aimed at the extermination of their oppressors. But working and living together in gangs of hundreds on the huge sugar-factories which covered the North Plain, they were closer to a modern proletariat than any group of workers in existence at the time, and the rising was, therefore, a thoroughly prepared and organized mass movement.

In the last part of this series, we’ll dig into what transpired during and after the Haitian Revolution. What happened to Haiti? Sugar production? How did colonists use God-talk to justify technologized exploitation in other pockets of their empire? And how does this history affect tech today?

Divine Innovation is a somewhat cheeky newsletter on spirituality and technology. Published once every three weeks, it’s written by Adam Willems and edited by Vanessa Rae Haughton. Find the full archive here.