“We should recall that metaphors matter,” writes scholar of religion Devin Singh. “Metaphors are neither vacuous redundancies nor merely ornamental language; they create and enhance systems of thought… Metaphors linger, ossify, and become embedded in social understandings and resultant institutions.”

Singh waxes poetic about metaphors and their religious and economic effects, especially where religion and economy dovetail. In Divine Currency: The Theological Power of Money in the West, Singh argues that Early Christian thinkers used Ancient Roman understandings of money and exchange in their homiletics, making for potent monetary metaphors like God as a pseudo-landlord (through God’s “providential management of the goods of creation”) and Christ as salvific currency. These mighty figures of speech, Singh continues, affected how Christian rulers like Roman Emperor Constantine managed both their economies and human subjects. Money became more than a workaday tool: it had Godly origins and ends, which, Singh posits, could explain the enrapturing place of money present day.

Chin up, shoulders back, I proudly concur that metaphors matter. Last month, I wrote “Bad Metaphors: Startup ‘Cults’” for Real Life magazine. I argued that calling a startup a “cult” diverts attention from the tech industry’s role in “bolstering exploitative supply chains, exacerbating unstable forms of employment, and working on behalf of violent, if not eugenic, state projects.” Startup-cultist language implies that other industries are more virtuous, as if capitalism writ large were basically innocent.

To avoid giving “cult” a runaway metaphorical power similar to what Singh describes for currency, I suggested nipping tech’s bewitching language in the bud. “As we abandon cult for less entangled language, we may need a return to more observational terminology like small business and profiteer as well,” I wrote. “A linguistic rapture could do us some good.”

That is, tech’s parallel lexicon serves mystifying and profitable ends. A “startup” is granted greater leniency than a “small business”; it’s defined by what it can be rather than what it is now. Salesforce recently acquired Slack, for instance, for 27.7 billion dollars. It still lacks any feasible path to profitability. The ability to react with a :party-parrot: emoji is not worth the GDP of Estonia; sry.

This newsletter’s previous issue dove into the nation-state metaphor as it is wielded imperfectly against tech giants. I contended that if these corporate goliaths were akin to any political form then they were city-states, and Vatican-esque ones at that. The city-state metaphor foregrounds the political power of the tech industry while also recognizing both its limitations and malleability; tech unicorns are capable of either intervening in political projects or staying above the fray as “neutral actors” when suitable and profitable.

We saw big tech acting in many ways like a city-state over the past two weeks. In the wake of the POTUS-sanctioned storming and occupation of the U.S. Capitol, perhaps the most significant, sustained political development has come in the form of mass deplatforming. Tech giants’ symbolic and material power now rings loudly as an eerie quiet: from the previous administration’s suspended Twitter accounts to shuttered MAGA Shopify storefronts. Big tech has abandoned far-right groups more than ever before because it's not profitable to remain in cahoots with them; the collapse of the nation-state—as an attempted coup makes clear—forecloses various channels for profit. Seeing like a city-state, the tech industry has decided to triage its affinities.

But—as this multi-issue metaphor-bender’s final volta—what lucidity would arise if we returned to more normative and quantitative language to describe tech’s burgeoning institutions? If tech companies were defined not by their missions to “connect the world,” or even their political prowess, but, rather, by their purses and policies, would (bewildering, wasteful) transactions like the Slackquisition still take place? And what if we centered “connection” and holism in our investigative approach? If we gave up defining tech by mere profits or harms, striving for descriptions more open, complex, human?

Paul Tillich, a “friend of the pod” of sorts, dishes some useful goss about the theological potential of language. Language about God in particular.

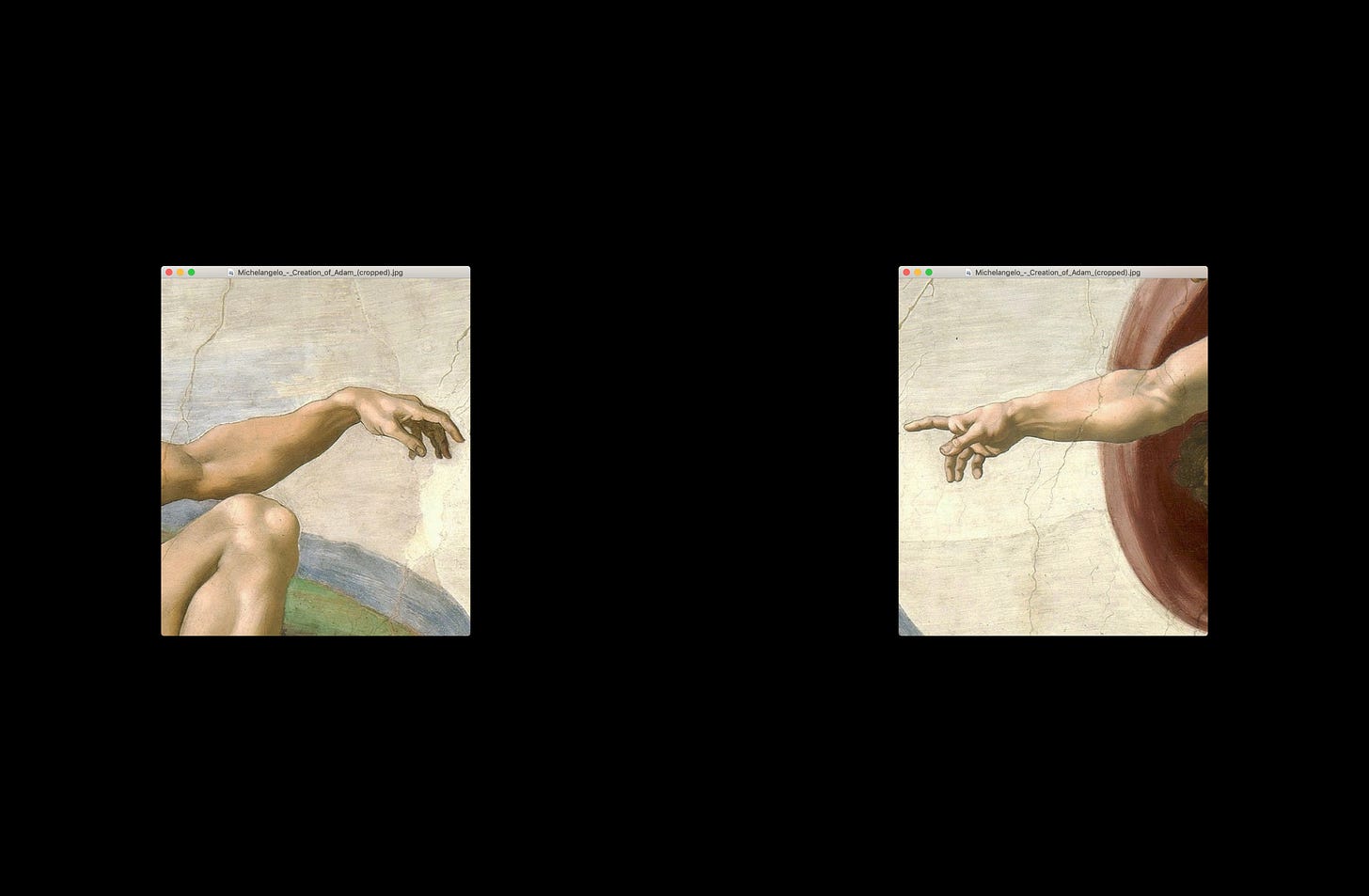

Descriptions of God (infinite, transcendent) depend on human language (finite, grubby). This is a double-edged sword. When God is referred to as “Father,” for example, this rhetorical strategy brings God “down” to the human relationship between father and child. “But at the same time this human relationship is consecrated into a pattern of the divine-human relationship,” Tillich suggests:

If “Father” is employed as a symbol for God, fatherhood is seen in its theonomous, sacramental depth… If a segment of reality is used as a symbol for God, the realm of reality from which it is taken is, so to speak, elevated into the realm of the holy. It no longer is secular. It is theonomous. If God is called the “king,” something is said not only about God but also about the holy character of kinghood. If God’s work is called “making whole” or “healing,” this not only says something about God but also emphasizes the theonomous character of all healing.

Our grubby language used to name God, therefore, is made shiny and righteous by virtue of its glorious, glorifying application. This line of thinking lends credence to Singh’s arguments about monetary metaphors. Naming God an economic administrator adds moral value to the financial realm and the kinds of relationships it rewards; Tillich would certainly concur.

I’m convinced that this transitive phenomenon applies to our descriptions of tech, too, especially its leaders who are in equal parts mythologized and reviled. That is, using “Musk” and his portfolio of companies interchangeably, for instance, conflates the figurehead with the corporate foundation that supports him. While this rhetorical slippage reduces corporations with massive material power to a lone figure, it also elevates the human stand-in to transcendental status, as if a human being were the abstruse, expansive, and unreachable tech company tout court.

Our semantic sloppiness further risks transmuting the titles and characteristics of corporate figureheads into aspirational identities. If Tillich is right, elevating Musk into a synonymous relationship with “his” publicly-traded companies risks glorifying the have-versus-have-not divide that the newly richest person on earth embodies. Elon “Yikes” Musk no doubt has magnitudes more power than you or I, and he is a keystone to his companies and their branding, but permitting the founder to envelop his inventions into his personhood grants him more power than he can actually wield alone. It deifies (self-obsessed, oligarchic, dare I say gluttonous) ownership in the process, making wealth inequality a chasm to be jumped rather than ruptured.

$TSLA shares jumped 700% over the course of 2020. This astronomical rise turned many of Tesla’s (and Musk’s) truest believers into millionaires. Dana Hull, a reporter at Bloomberg (yet another man-corporation singularity), profiled Brandon Smith, a Wisconsinite who, after his mortgage applications were rejected because he lacked a credit score, poured all his savings (around $80,000) into Tesla stocks. His portfolio is now worth more than one million dollars plus or minus a few hundred thousand dollars—“depending on the day,” he said.

Smith’s interview signals that, to him, Tesla, and subsequently he, would be nothing without Musk. Elon is the “smartest engineer,” Smith argued. He said people who dislike Musk—for instance, those who criticize how Elon gunned to overthrow Bolivia for its lithium—don’t read the news carefully. Instead, they lazily read headlines and gloss over how honest Musk is to a fault. Though the first gilded ship has sailed, “we’re only at the beginning.” Identifying as part of the in-crowd, Smith implies that there is still time to convert to the cause.

This stated faith in a founder can drive us in several directions at once (unlike a Hyperloop or SpaceX rocket). Turning again to Singh’s Divine Currency suggests that Smith approaches his proselytizing as a moral undertaking. He saved himself from one failure of capitalism—the blood-sucking mortgage industry—by turning to a “miracle” of the marketplace. That salvific potential remains if you, too, open your heart to it. He once was lost; but now he is found.

“Once a metaphor has become fully entrenched and assumed within a framework or thought, it may sometimes be described as dead,” Singh writes, drawing from Nietzsche (woof). “I would characterize dead metaphors as coins that have lost their pictures yet still function and circulate as coins… They continue to enable transactions (of meaning) but have lost their distinctive imagery and evocative power.”

Could this, coupled with the dead-horse-beating use of “missions,” “conversions,” “angel investors,” and so forth, help partially explain why the tech world’s lexicon is tolerated, but not necessarily embraced by all? Does it elucidate why Smith’s deadpan interview is far from a sermon in tenor despite a salvific slant?

No system is all-encompassing: that includes capitalism, David Graeber noted in Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Different logics exist and thrive therein. Neither is language a totalizing or self-sustained system. The superimposition of capitalism and language—like, idk, who has two thumbs and writes a series of smooth-brain sentences on Google Docs and then shares them via Substack—makes for slippages as well as the occasional deadening cliché. Comms teams continue to deploy “connection” and “innovation” as one-size-fits-all moralizing justifications for banal profiteering processes like the proliferation of data-thirsty Snapchat stories-esque schemes across social media networks (wtf are “fleets,” @jack), or, to circle back to Musk, digging tunnels. Likewise with “content” as used to describe everything. Our language can rush to sanctify the most earthly concepts; it can fall flat.

If our uninspiring language sucks and fails to accurately describe what harms exist, then what semantic tools remain at our disposal?

Chase Berggrun, in her splendid essay about poet Paul Celan, offers a lifeline somewhat removed from the intricacies and imperatives of the market:

To paraphrase Giorgio Agamben, magic is speech liberated from language, and the later poems of Celan swim in that realm of magic. In these poems, Celan bucks against the way that descriptive language can collude with power to elide the ways that language itself transforms experience, replicating current orders while wearing a mask of neutrality. Instead, he engages in a kind of description: an unwriting of the world, in pursuit of an elsewhere. This elsewhere is not ahistorical. As Celan says in “The Meridian,” discussing how each poem springs from and is indebted to the moment that produced it: “[The poem is] language actualized, set free under the sign of a radical individuation that at the same time, however, remains mindful of the borders language draws and of the possibilities language opens up.” Indeed, the magic of the poem offers a way to speak and reach another in a manner quite unlike any other kind of writing.

Can we shift language or shape poetics to describe the place of technology, of technogarchs—let alone other structural or individual monsters—with both lucidity and urgency? Making for an unwriting of our world in pursuit of a more just elsewhere?

If so, how can we describe figures like Musk and their power? Could we name them, perhaps, by listing their employee rolls or bank accounts? Name them as unabridged infrastructures? Their blood type and DOB, as administrators would an injured employee-cum-inpatient at a hospital? Employees’ favorite colors in an unabridged list? How can we upend the corporate-corporator relationship, word first, revealing the fleshy, the material, the commodity behind the fetish?

I—like any good pontificating penman—have taken my prescription and run with it. This newsletter’s “metaphors” chapter ended, we’ll hop onto another thematic train in issue [13.0]. For now, dear reader, we beat on, boats against the current. Among the verbal flotsam and informational jetsam, hoping we can build novel narrative arks with more torque, more backbone, floating over the drivel that is marketspeak.

Divine Innovation is a somewhat cheeky newsletter on spirituality and technology. Published once every three weeks, it’s written by Adam Willems and edited by Vanessa Rae Haughton. Find the full archive here.