I’ll say it loud; even as a Seattle resident, I’ll say it proud: we need more TV shows and books that investigate (and occasionally pooh-pooh) the Seattle tech world. Silicon Valley holds a monopoly as the setting of this genre, with HBO comedies and literary memoirs galore. Seattle can boast insincerely of Grey’s Anatomy, which ostensibly takes place in the rainy city but is actually filmed in… California. Ditto for Frasier. QED.

Besides TV and books, there are historical reasons why “tech” is synonymous with “Silicon Valley” in the US hive mind. Fred Turner’s From Counterculture to Cyberculture (which this highbrow newsletter recommends) describes the Bay Area as the breeding ground for tech culture: the lovechild of World War II military research groups and widely-publicized countercultural beliefs expressed in episodes like San Francisco’s Summer of Love.

California is the birthplace of—if not also the wedding venue and honeymoon suite for—the ideologies and outcomes that we associate with tech today. Grandiose ideas of saving the world through “innovation,” yet an appalling track record for actually walking the talk.

The beliefs that sustain this track record have a name: The Californian Ideology. Coined by media theorists Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron in 1995, the term refers to the mix of libertarianism, techno-determinism, and progressiveness-in-name-alone that defines the Valley’s corporate ecosystem (and now beyond).

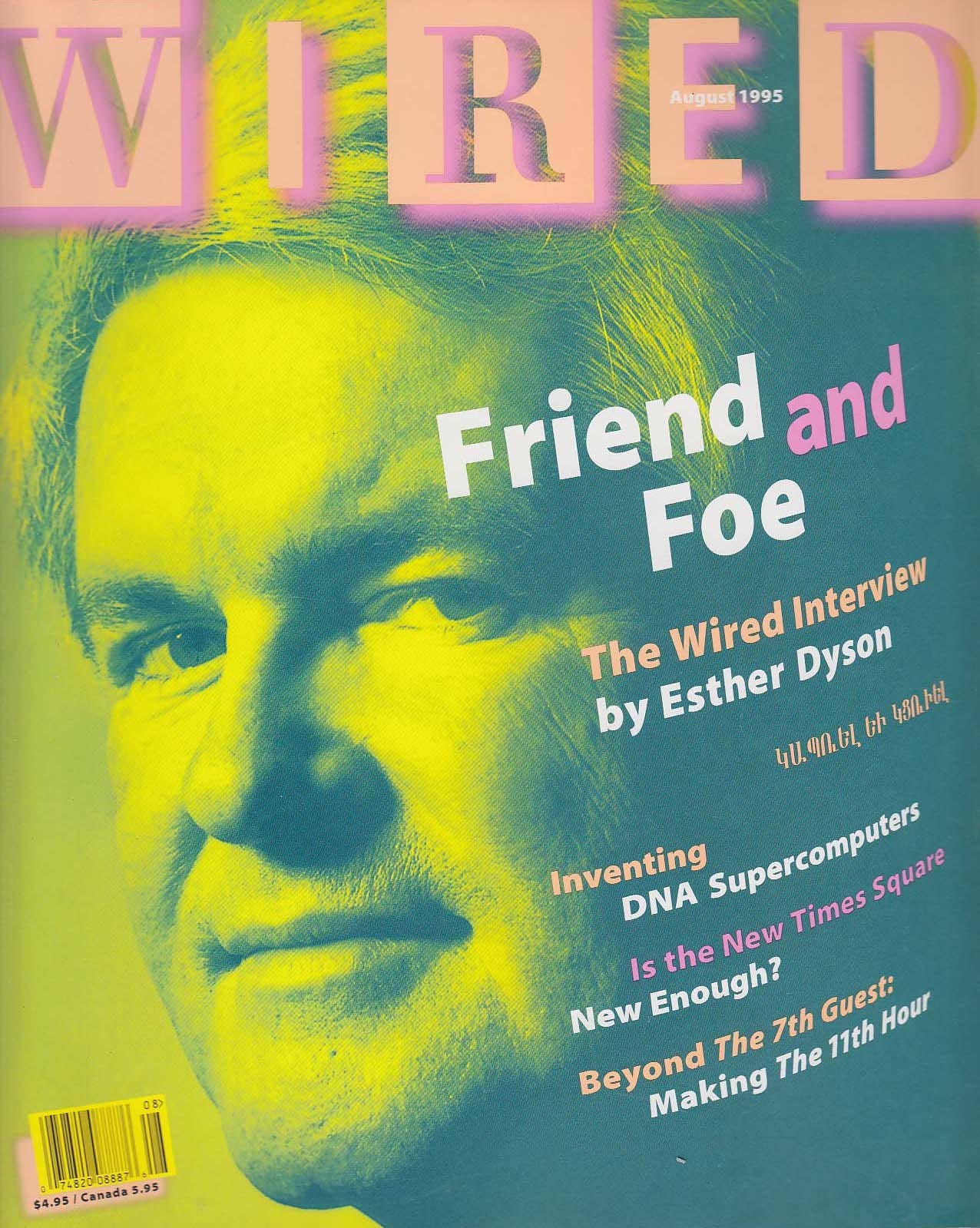

Barbrook and Cameron liken this genesis to a religion, at least semantically. They use religion’s vocabulary to refer to Marshall McLuhan, who predicted that the World Wide Web would usher in an age of “electronic direct democracy,” calling him the “patron saint” of this movement; and Howard Rheingold, who believed that tech workers were the vanguard of modern social liberation, its “guru”; and tech magazine Wired “the monthly bible of the ‘virtual class.’”

Conservatism lurks behind these utopian views, Barbrook and Cameron argue. In the 90s, Wired deified Newt Gingrich (smizing above) in a series of laudatory pieces, ignoring his penchant for welfare cutbacks, “instead mesmerised by [his] enthusiasm for the libertarian possibilities offered by new information technologies.” The theorists posit that this affinity solves not for the “electronic agora” of cyber-democracy, but rather “the apotheosis of the market, an electronic exchange within which everybody can become a free trader.” They continue:

In this version of the Californian Ideology, each member of the 'virtual class' is promised the opportunity to become a successful hi-tech entrepreneur. Information technologies, so the argument goes, empower the individual, enhance personal freedom, and radically reduce the power of the nation-state …

In other words, despite the utopian theorists that supposedly drive The Californian Ideology, the Ideology’s core cultural institutions fawn over and support elected officials that want to deregulate the economy. These figures seek to create an atrophied nation-state that must contend with other institutional bodies that vie for political power. Has this prophecy come true?

To answer this question in full requires appreciating what a nation-state is. Explains scholar of religion Sara Kamali, “The term nation-state reflects both a geopolitical and a political entity. Nation refers to a sociocultural entity—peoples who share the same culture, history, and language; state refers to a legal and political entity that is a defined sovereign territory.” The nation-state is therefore more than just a physical boundary: an ethos and pathos suture the people and institutions within those boundaries, a dyad that shapes political machinery and is shaped by this very machinery in turn.

Historians point to the Treaty of Westphalia (1648), the formal conclusion to the Thirty Years’ War, as the beginning of this political form. The stipulations therein hinged upon the existence of clear sovereign territories like a nation-state or empire, effectively replacing the city-state (or polis) structure that preceded it, in which a local government stated loyalty to an absent monarch or other figurehead. The Treaty also weakened the power of the Pope as political arbiter.

Kamali suggests that various products of globalization may threaten the nation-state. Its hold weakens if people identify with other entities and concepts above nationality, whether smaller (like Texas) or larger (like the EU or “global citizenship”). Changes in economics, communications, and warfare all fuel these shifts.

Such developments, as well the proliferation of The Californian Ideology beyond the golden state’s borders, lend credence to those who approach tech giants as de facto nation-states and warn of their considerable political muscle.

The traditional nation-state may have grown nominally in power, with tech companies as loyal allies: Google has been known to get kissy-kissy with the CIA’s venture capital wing; Clearview AI is police state surveillance on steroids; and Palantir continues to partner with ICE. But, nodding to Barbrook and Cameron’s prophecy, the influence of the de jure nation-state perhaps pales in comparison to the awesome ascendance and runaway political, social, and economic influence of tech companies. Tech unicorns offer everything from pharmaceuticals to transportation; they have GDPs larger than those of entire subcontinents; they decide what political violence is acceptable and can upturn elections.

Yet this nation-state metaphor begins to wobble when we (finally) pivot our gaze to Seattle, Silicon Valley’s second fiddle. Digging into Amazon as a sample size of one suggests that, of any political category, tech giants are more like city-states than nation-states. And, if we are to qualify their city-state form, they’re decidedly Vatican-esque.

Since its foundation as a white settler colony in the mid-nineteenth century, Seattle has undergone a series of booms and busts. Timber, gold, and aerospace have all preceded tech as keystone industrial powers. Microsoft’s move to the area in 1979 initiated the bluechip dynasty that defines the metropolis today.

At the same time that the city has seen flocks of tech companies move in, leading to skyrocketing rents and housing shortages that make it increasingly precarious for those who don’t work in tech, the metropole has also witnessed the encroachment of these very companies into the service provision domain.

Few programs epitomize this phenomenon as clearly and urgently as SCAN, a Seattle-area at-home coronavirus testing and tracing initiative. It is funded by Bill Gates and uses Amazon’s logistics network for distribution. Originally only for Seattle’s King County, SCAN has now expanded its coverage to also include Tacoma’s Pierce County to the south. Both Microsoft and Amazon have replaced many of the roles that a public health service would play alone in a crisis like a pandemic, with American civic structures too atrophied by decades of Gingrich-y neoliberal policies to carry the load.

National press coverage highlights how Amazon and Microsoft led by example as tech corporations that “listened to science.” The New Yorker reported that both companies closed their Seattle-area offices when there were “only” a dozen recorded Covid-19 fatalities in the United States. The administrative decision meant almost 100,000 fewer people commuted in the Seattle area every day; the city hunkered down weeks before New York did, potentially saving tens of thousands of lives.

But public health initiatives and eerie physical absence are not the most visible markers of the two tech giants’ joint dominance over the city. That honorific belongs to Amazon alone in the form of hundreds of Prime-logoed Mercedes Sprinter vans that trawl the streets. The same vehicles that are the face of homesteading-ish #vanlife culture supply almost every good or service that a quarantined person could need, from food, to pills, to TV shows, to ant farms (which are like sourdough but more dynamic). The breadth and depth of Amazon’s coverage suggest that the corporation’s domain is the entire city. Amazon as a polis.

Certain qualities may appear as lacunae to this line of thinking. For one, Amazon’s power clearly exists beyond the Pacific Northwest. The company has plots of territory scattered across the globe in the form of warehouses. Wherever you read this, it’s possible that your recycling bin is stuffed with crushed boxes adorned with the company's arrow-smile logo, an icon-mosaic and disembodied reminder of Amazon’s might at any stage of the consumption life cycle.

The company’s human figurehead, founder and CEO Jeff Bezos, enjoys power outside the polis, too. Most visibly, we all know, as the richest person on earth. But, not one to let capital go unleveraged, Bezos has mustered his vast resources to further expand his personal influence through self-serving "philanthropic" initiatives as well as ownership of The Washington Post. He holds sway across civic arenas, determining whether “democracy dies in darkness” and how.

And, of course, Amazon is still dependent on formal political decisions and structures that allow it to reap profits and grow as aggressively as it does. It spent millions of dollars on lobbying efforts last year. It enjoys a love-hate pseudo-symbiotic relationship with USPS. And it pays almost nothing in taxes.

But these seeming exceptions are consistent with a particular iteration of the city-state: The Vatican. There’s a litany of more obvious shared qualities: immense wealth, small sovereign territory enveloped by a larger nation, global reach, powerful and ubiquitous iconography, a (stated) commitment to charity, and more. Less obvious characteristics in common, too, like the fact that individuals can encounter both institutions on a personal level, whether spiritually (confession) or algorithmically (“Recommended items similar to your past purchases”). Or the convenient capacity to be at once ecumenical and abnegating, deciding when to make universal claims or remain “objective” and above the fray of certain sticky political questions.

The Treaty of Westphalia once lessened the role of the Vatican in the political fabric. If Amazon’s political and institutional covalence is representative of a larger truth, then the nation-state has to contend with another kind of polis with global tendrils.

“Elected politicians sense a new form of power is starting to eclipse their own, even if they don’t know exactly what to name the source or the effect,” argues tech researcher Alex Rosenblat. She identifies mobilizations against the privacy violations and antidemocratic ambitions of tech companies as a new iteration of the American accusation of government overreach, which “suggests that we are looking towards tech companies to usher in new forms of governance.” A “cultural transference” on a national scale.

Perhaps this pivot will lead to new sites of cultural inquiry. Seattle or some other oracular locale may get the prophesying status it deserves. Maybe a TV show or tome, too.