Divine Innovation covers the spiritual world of technology and those who shape it. It’s published once every three weeks, and is written by Adam Willems.

Being at a theological seminary as someone with no intention of being ordained means I straddle an insider/outsider position all the time. I could describe (at length) the benefits and pitfalls of my experiences, but I think I’ll save the solipsism for later in my journal.

One of the most instructive parts of my experience at Union Theological Seminary has been the chance to see the inner machinations of an educational structure for clergy-in-training. [I’ve also had the chance to spend some quality time with some cool, verging on creepy, winding, stone staircases.]

Seminaries try to offer the tools an ordained person might need to respond appropriately to spiritual crises. As figureheads for their respective local communities, religious leaders have to understand when to intervene, how to intervene, and when to avoid crossing a line into personal issues.

To be clear: according to religion, denomination, political alliance, and other factors, these strategies and lines in the sand can be wildly divergent. The results vary, to say the least.

But there are frameworks that I have learned in classes like Introduction to Pastoral Care that are useful for analyses of crises and caregiving methods beyond explicitly religious places.

One of those is the idea of the “identified patient.”

Ok first: it’s certainly possible that some of you have heard “identified patient” used in other, more clinical, contexts. Pastoral caregivers do not have exclusive domain over the concept. It’s also used widely in therapeutic settings related to family issues.

The Dictionary of Psychopathology—a page turner in its own right—defines the term in an irredeemably mealy-mouthed way (boo!). So I’ll paraphrase:

An identified patient is the person within a family that is seen as the “problem” by other relatives. Sometimes this judgment is accurate, but the identified patient is often misdiagnosed and projected upon by the rest of the family. Someone else—or the entire family—is actually causing the issue.

For example, a family’s adolescent child may be spoken of as a problem by other relatives; the child has acted out in school and their grades have dipped. The teenager is the “identified patient” of the family, even though the real problem is the parents’ messy divorce. The “identified patient” label speaks both to symptom and cause.

Maybe you identify (so to speak) as the identified patient of your family—and maybe you have frosty and/or estranged ties to your relatives as a result. In my class, people spoke of their own experiences as the identified patient of their families; it helped them understand that the way others saw them was highly contextual and subjective. Their family’s scrutiny and disdain wasn’t their fault.

I find this term useful insofar as it directs us to think about why certain people become the focus of gossip and disdain. It’s as much, if not less, about the identified patient than it is about the conditions of those projecting onto them.

For Divine Innovation, the idea of the identified patient can be helpful if we widen its scope beyond the family. It holds promise as a useful lens to analyze popular discussions around technology and related social developments.

Let’s mull over ventilators.

In what feels at once four days ago and three years ago: remember when every headline (and all of the cortisol in my body) asked whether the US government would run out of ventilators?

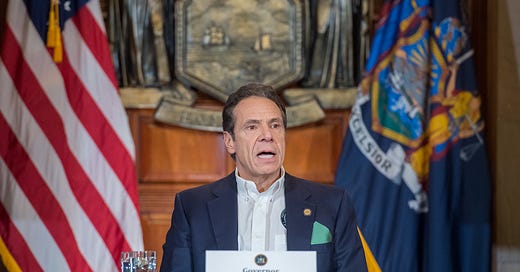

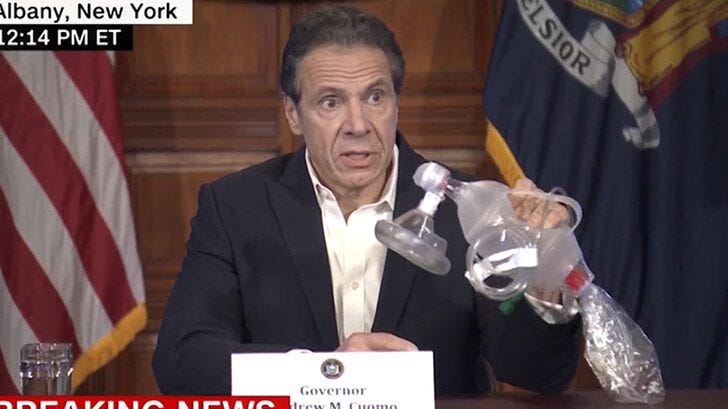

Cuomo remembers.

For weeks at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in New York, Governor Andrew Cuomo’s daily press conferences spent many long, long minutes discussing available stockpiles of ventilators and his efforts to acquire more of them. New York State saw what had happened in Northern Italy, where a ventilator shortage forced doctors to decide which COVID-19 infected people lived and died. Despite the apocalyptic precedent in Italy, leaders in Albany, New York City, and Washington, D.C., still decided to bicker and politicize the necessary shutdown of New York City and State, leading to tens of thousands of deaths. Responding to a crisis largely of their own design, state machinery went to great lengths to acquire more ventilators and ensure that everyone who needed access to life-saving medical care and technologies could receive it (with a hefty bill at the other end, obvi).

Though clearly central to treatment, the ventilator became the identified patient and at the same time a silver bullet. If New York could get enough ventilators, the thinking went, then lives would be saved and the long-term consequences of the pandemic would be substantially less than they would be otherwise. The technology would save us, and save all of us.

By positioning himself against the federal government, Cuomo’s seemingly herculean efforts afforded him popularity as a Democratic figure. He exhausted himself looking for ventilators to save his state’s people. He interviewed his COVID-19 infected CNN-anchor-and-brother Chris. On the (hopefully permanent) tail end of the pandemic, the ventilator shortage a thing of the past, Cuomo announced last week that he’s publishing a book on the blow-by-blow, behind the scenes efforts of his trademark New York Tough™ resilience and response to the public health crisis. He’s begun taking victory laps.

With ventilators as the problem child subsequently handled, this technological incarnation of the identified patient took on a spiritual power, with a literal life(-saving) force that said less about its technological capacity than it did about the human discourse and projection surrounding it.

I’m not here to make a conspiracy theory, we have enough of those already. But it is telling of politics—and the scores of social issues that led to the COVID-19 pandemic in the first place—that a shortage of ventilators became the defining issue for several weeks. A totally atrophied public health system mattered less; mangled, frayed geopolitical relations mattered less; the astronomical cost of privatized healthcare mattered less; a disastrously bungled political response mattered less. The identified patient was a “crisis,” and needed our undivided attention.

With so much talk about broken economic systems, political systems, public health systems, etc., it’s maybe unsurprising that a useful person to talk about is Marx.

I took an incredible, eye-opening class with Ajay Singh Chaudhary last year, an intensive course on Marxian thought. I was Ajay’s student before I started my coursework at Union Theological Seminary; reading some of Marx’s corpus prepared me for the labor of analyzing canonical religious works. Just like those scriptures, Marx’s writings are subject to a wide range of interpretations and applications. Ajay posits among these a thought-provoking (and I think accurate!) understanding of Marx’s thoughts on religion as an “opiate of the masses.”

Reading the passage in the context of the larger essay in which it’s situated, it seems that Marx is not arguing that religion is a drug, something people get addicted to, is toxic. Instead, his point is more that religion is almost a pressure valve. People release their earthly worries onto a transcendental realm beyond the here-and-now. It’s politically useful as a way to get people to pay attention to the sacred other-place, rather than identify and mobilize around the struggles that they experience on earth. In other words, religion seems to function as an identified patient: people project their own issues onto another entity, in this case a deity, as a way to eschew more substantive engagement with their own issues.

Ajay pointed out that many communist leaders seemed to approach religion through this pressure-valve, identified-patient lens. Tito of Yugoslavia, for instance, did more than just tolerate the presence of religion within his communist state: he built (brutalist) mosques and churches with the understanding that, as long as the state could not fulfill all the material and social needs that its people required, religion was a useful tool to defer justice and displace blame and unrest. Religion can be structured by state powers, and its derivative strategies can be used to retain power in a range of political projects, from Tito (through buildings) to Cuomo (through technology).

It’s worth ending with a reading from The SAGE Encyclopedia of Marriage, Family, and Couples Counseling (seriously). The text defines “identified patient” in a way that meaningfully departs from the way it’s framed by the dictionary above.

The identified patient (IP) is the individual in the family or couple whose problematic behavior triggers the family or couple’s motivation to seek therapy.

With this framing, is a ventilator still an identified patient of sorts? Maybe not entirely. But in this context, the systemic issues surrounding the rampant shortage of ventilators in New York, the US, and beyond, become the problematic behavior that triggers a call for change. Political mobilization, calls for accountability, are demands for care. They’re understandings of braided, common political futures that necessitate telescoping out beyond the individual, the ventilator, the family, or any one (narcissistic) governor or president.

I learned about these concepts in a seminary that felt at once hallowed and removed. Spiritual crises, their symptoms and causes, shouldn’t just shape the conversations, interventions, and outcomes made in those halls. They should affect what happens in bastions of political power, in Tesla workshops, in broad daylight. Technology can clearly be used as an identified patient for political deflection and gain. Maybe responses grounded in caregiving aren’t a silver bullet, but they’re definitely worth their weight in gold.