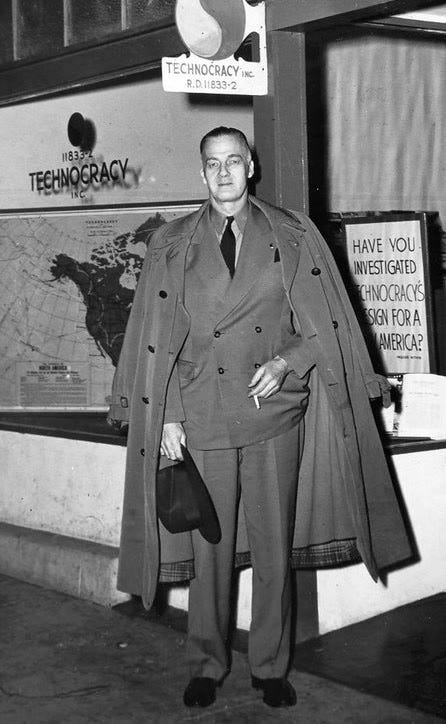

The previous issue of this newsletter peered into the past of the Technocracy movement, a (white- and) STEM-supremacist political group that aspired to smoosh Canada, the U.S., and Mexico into a giant vertical supply chain run by a cabal of Very Objective Scientists. With a kooky fake-engineer-cum-fake-businessman named Howard Scott at the helm, the movement boasted 500,000 members at its peak—before totally crashing.

I did a sneaky thing in issue 27.0's concluding teaser by implying that Technocracy’s disintegration was noteworthy or cinematic. Fire-and-brimstone explosions? Lower your expectations, honey!

Here's the harsh truth about the Technocracy movement's death and its semi-total disappearance from collective memory: People just stopped taking it seriously! The Kony 2012 of the 1920s and 30s, lol.

Finn Brunton of Digital Cash couches this reality in kinder terms: The Technocracy movement found itself “marooned in time.” Increasingly irrelevant while the world moved on and lost itself to new concerns. Why rally around the erg-forward readjustment of prices when, say, Nazis exist and the world approaches war? (Not to say that capitalism and fascism make for strange bedfellows.)

The movement's understated demise teaches us tons, especially with respect to contemporary movements that wield (1) new currencies and (2) "rational utopias" like Castor and Pollux to sail us out of turbulent times. The larger context of Technocracy's era, including its rapid denouement, also clarifies how political turmoil can distract from, and then shatter, a burgeoning "utopian" vision. Intentionally or not, governments cause chaos; are they trying to prevent the end of their economic realms?

In Digital Cash, Brunton explains the Technocracy movement's currency fetish through the theory of the "cosmogram." The term was first coined (oop!) by historian of science John Tresch: "an object that contains a model of the universe and a plan for how to organize life and society accordingly."

Many cosmograms claim religious origins. Brunton mentions "the Biblical Tabernacle, Dogon rites, and Tibetan Buddhist mandalas." Cosmograms writ large hold the following traits in common:

From a user's perspective, [the cosmogram] situates us in time and space (where and when are we?), establishes ontological levels (what is important?), and provides practices and models (what should we do and how should we understand?)… In addition, it offers an image of the world as it could be, and it makes that image concrete with a set of practices and rituals to guide participation in the world—actions you can actually take. It is a model of the world with an agenda, an implicit utopian project expressed through an arrangement of objects and symbols.

In the case of the sacred examples mentioned above, this manifests itself in the form of particular doctrines, chosen people, collective pursuits, aspired states of being, activities, or a combination/subset of the aforementioned variables. Tabernacle, rite, and mandala are all things and ways of being in the world.

This artificial construction encourages parsing "religious" cosmograms from their "secular" counterparts. Thank Protestantism for such binaristic hubris! If we discard the dyad, we can see that religious and "non-religious" cosmograms alike are idolized and worshipped and demand conversion.

The Technocrats' currency prototype, the "energy certificate," is definitely a cosmogram, at once a "document and object." A "cultural technology." The movement's proposed cash successor was both literal: a physical certificate corresponding to units of energy; and aspirational: a (potentially) revolutionary tool. Upending the economy's speculative and nonsensical attachment to capitalists' profit margins in favor of productive distributions of goods and services—bringing some sort of placid material justice. All through the simple genesis of a new money. Aspiring to convert one’s cash into energy certificates portended a conversion in worldview and political agenda.

The idea of the cosmogram, paired with the turbulence of Howard Scott's time, explains how Technocrats gained influence. Faced with the shitty and scary conditions of the Great Depression, apostates saw a multiplier effect in Scott's cosmogram. It offered a (literally) legible and easy techno-fix. It's the money, stupid! echoes Scott's refrain. If money's avatar changed, then other dominos would fall and usher in political and social and even biological change. (Or, to be more precise, eugenic change: recall Scott's racist screed!)

I'm bringing physics into the mix here for Divine Innovation's first and last STEM lesson. The Technocracy movement's life history boils down to potential energy and momentum. The group's ranks could swell because of discontent and mayhem. It collapsed because of interrupting chaos and the retrospective inadequacy of its static doctrine. Forces clashed and Scott's party disbanded.

Brunton concludes that it's easier (and ultimately more successful) to assemble a vision for the future than it is to implement a technology before its time. Howard Scott was a white supremacist and a con man but his currency had a point! When media outlets go balls-to-the-wall in covering "inflation" without considering stock buybacks, crrrrreamy profit margins, pro-creditor policies, vulturistic debt mongerers, defense spending, capitalism-caused climate change, or binders full of other variables, it's clear that money is broken and fake af!

It's therefore no surprise that cryptocurrency evangelists consider themselves the early adopters of our realm's new coin—and that, before its technology has actually proven workaday utility or stability, the movement's beliefs and culture have catapulted blockchain-based monetary instruments into legitimizing fora. The crypto world is trying to launch its society before its stack really lands anywhere.

In this series's closing essay, I'll dive into the specifics of the crypto realm. What do its high priests really believe? How may contemporary empires react?

Stay tuned bb <3

Divine Innovation is a somewhat cheeky newsletter on spirituality and technology. Published once every three weeks, it’s written by Adam Willems and edited by Vanessa Rae Haughton. Find the full archive here.