If you’re wondering what the Democrats—who hold the White House, House of Representatives, and Senate—are doing while everything is falling apart, please stop worrying and thus killing my vibe?? The Aspen Institute will save you, thanks :)

What is to be done with all the bad content? In March, the Aspen Institute announced that it would convene an exquisitely nonpartisan Commission on Information Disorder, co-chaired by Katie Couric, which would “deliver recommendations for how the country can respond to this modern-day crisis of faith in key institutions.” The fifteen commissioners include Yasmin Green, the director of research and development for Jigsaw, a technology incubator within Google that “explores threats to open societies”; Garry Kasparov, the chess champion and Kremlin critic; Alex Stamos, formerly Facebook’s chief security officer and now the director of the Stanford Internet Observatory; Kathryn Murdoch, Rupert Murdoch’s estranged daughter-in-law; and Prince Harry, Prince Charles’s estranged son. Among the commission’s goals is to determine “how government, private industry, and civil society can work together . . . to engage disaffected populations who have lost faith in evidence-based reality,” faith being a well-known prerequisite for evidence-based reality.

This reassuringly sassy block quote comes from journalist Joseph Bernstein, whose excellent essay “Bad News” surveys the wreckage that is disinformation studies. He depicts the tangled relationships in which disinformation specialists, private universities, national news networks, philanthropic foundations, and tech giants both butt heads and cuddle. Not my kink! Despite their various motives, these factions share something in common: a desperate faith in techno-solutions.

On a macroscopic level, Bernstein argues, techno-determinism links most social ills to “the algorithm,” which also serves as its own antidote.

Behold, the platforms and their most prominent critics both proclaim: hundreds of millions of Americans in an endless grid, ready for manipulation, ready for activation. Want to change an output—say, an insurrection, or a culture of vaccine skepticism? Change your input. Want to solve the “crisis of faith in key institutions” and the “loss of faith in evidence-based reality”? Adopt a better content-moderation policy. The fix, you see, has something to do with the algorithm.

This both/and faith didn’t emerge out of the ether. That is, the sudden omni-attribution to the algorithm isn’t the algorithm’s own doing. Instead, Bernstein traces the belief in such base, human malleability to the ad industry. Vance Packard’s The Hidden Persuaders, published in 1957, depicted ad men as “wielding some unholy concoction of Pavlov and Freud to manipulate the American public into buying toothpaste.” The book helped convince the public of advertising’s inherent exploitativeness, while, in reality, doing little to prove that ads really work (which they don’t, tbqh). Instead, as something of a native ad itself, The Hidden Persuaders helped convince businesses of the effectiveness of ads, helping the ad industry see its rolodexes and revenues swell. Mythmaking about mythmaking works, baby!

Bernstein seems to argue that a techno-solution is little more than a faith in the status quo and one’s extant position within social hierarchies. Disinfo researchers and fact-check-y media folks, for instance, should answer long-unaddressed and uncomfy questions like: “Is social media creating new types of people, or simply revealing long-obscured types of people to a segment of the public unaccustomed to seeing them?” Office hours and wine and cheese nights are only so inclusive.

Techno-solution worship—that is, belief that the only problem with disinformation involves the wrong information being delivered to screens—points to a ritual somewhere between a self-coronation and a renewal of vows. It also absolves milky, rich whiteness. “It's possible that the Establishment needs the theater of social-media persuasion to build a political world that still makes sense, to explain Brexit and Trump and the loss of faith in the decaying institutions of the West,” Bernstein writes.

In a way, this world is a kind of comfort. Easy to explain, easy to tweak, and easy to sell, it is a worthy successor to the unified vision of American life produced by twentieth-century television. It is not, as Mark Zuckerberg said, “a crazy idea.” Especially if we all believe it.

I’ve given Bernstein so much space in this issue for a few reasons. One, I liked his article. Two, I reached out to him for an interview and he didn’t answer, which = womp womp :( But three, and most importantly, the essay resuscitates an inquiry central to this newsletter: what role does faith play in tech? Bernstein offers us a side door: investigating tech critics’ beliefs, who, whether or not they do so on purpose, assign massive ontological power to blue-chip companies. This helps tech platforms convince businesses that their ads actually work. Feeding the monster by calling it the monster.

Tech derision often adopts brainwashing rhetoric. In Disrupted: My Misadventure in the Startup Bubble, writer Dan Lyons details his time at the marketing software company HubSpot. “HubSpot is like a corporate version of Up With People, the inspirational singing group from the 1970s, but with a touch of Scientology,” he writes. “It’s a cult based around marketing. The Happy!! Awesome!! Start-up Cult, I began to call it.” Ridiculing the company’s former chief marketing officer for his delusions of grandeur, Lyons charges, “He’s brainwashed. Better yet, he has brainwashed himself. He has mixed his own Kool-Aid and drunk too much of it.” He notes how some employees repurpose shower rooms into “sex cabins,” and how newcomers undergo training sessions akin to “brainwashing” rituals.

And I, decidedly unlike Dan Lyons insofar as I possess neither a personal website nor a (self-identified) storied career as the author of two of the most important recent books about Silicon Valley, have been known by a much smaller readership (you, perhaps!) to opine within this “cult”-startup analytical nexus. I stand on the shoulders of Lyons nevertheless, having worked as a culture intern at HubSpot in the months succeeding Disrupted’s publication. I even leafed through his book in the week leading up to my start date. My subsconscious soon deleted memories thereof, however, following a bike-commute-cum-hit-and-run that ended not with a chaste, cooling shower in an erstwhile sex cabin, but, rather, with my face planted on the hood of a car (and asphalt thereafter).

Yet similarly to Lyons’s gig and subsequent screed, my eighteen-month tenure at a fintech startup begat startups-are-“cults” suspicions of my own. Inquiring what separates “cult” from startup, religion from economy, brought me to Union Theological Seminary, a perch from which I could begin to analyze and process my own experiences in the spiritual trenches of the New Economy as well as the larger religio-economic landscape. Assuredly, though negligently and prematurely, I began to publicly outline my hypotheses in “cult” terms: “every bit of cult scholarship that I’ve read since has deepened this conviction,” I wrote in this newsletter’s opening salvo. The company’s obsession with its founding myth divorced from fact as well as its dogged commitment to growth at any cost led me to this assessment. The conviction soon collapsed, as we know (here and here).

Brainwashing rhetoric, perhaps unsurprisingly, latched onto the American imagination around the same time as The Hidden Persuaders. The 1962 film The Manchurian Candidate (pictured below) took cultist fear and let its freak flag fly. It seized viewers’ anti-communist and orientalist fears; in it, a white American soldier is brainwashed by “the Chinese” to assassinate a sitting U.S. senator. (Racist and Christian-supremacist “anticult concern” had existed since at LEAST the 1930s: at that time, Detroit police dubbed the Nation of Islam a “weird Voodoo cult.”)

By 1987, the American Psychological Association would explicitly reject brainwashing theories as lacking “scientific rigor and even handed critical approach,” prone instead to “sensationalism in the style of certain tabloids.” But the damage was done and continues to scar us! Brainwashing isn’t real—coercion and group pressure are, for sure—but here we are still talking about it like it doesn’t come from some real McCarthy-esque stinky movies and attendant scammers.

So, as scholar of religion Dr. Megan Goodwin said in an interview with (silly) me in Religion Dispatches about QAnon:

For me it comes back to this assumption that “cults” equals brainwashing, so people have been tricked or forced into behaving this way rather than making decisions that seem logical to them. Internally consistent worldviews are a thing, and they’re making choices. They need to be held accountable for the choices that they’re making.

No one’s forcing them to consume this media. No one’s forcing them to be out in the streets, and certainly no one’s forcing them to take rifles into the non-existent basement of Cosmic Pizza in DC. It’s an extension of the way that we talk about Fox News, too. We’re like, “Oh no, my dad has been brainwashed by Fox News.” No, your dad is an adult human who made a choice to turn on rabidly biased news, and it has become a habit. It’s a way that he is in the world. And he made choices based on that choice. So there’s an accountability piece there.

Popular understandings of religion affect more than just religion. The Protestant emphasis on “faith alone” magnifies the power of beliefs over practices in other contexts, too. In the case of the anti-vax movement, for example, scholars have come to conclusions like the following: “Recognizing disingenuous claims made by the anti-vaccination movement is essential in order to critically evaluate the information and misinformation encountered online.” Is sincerity really the problem, though? Like, does believing in your lies determine the effects of spewing bullshit?

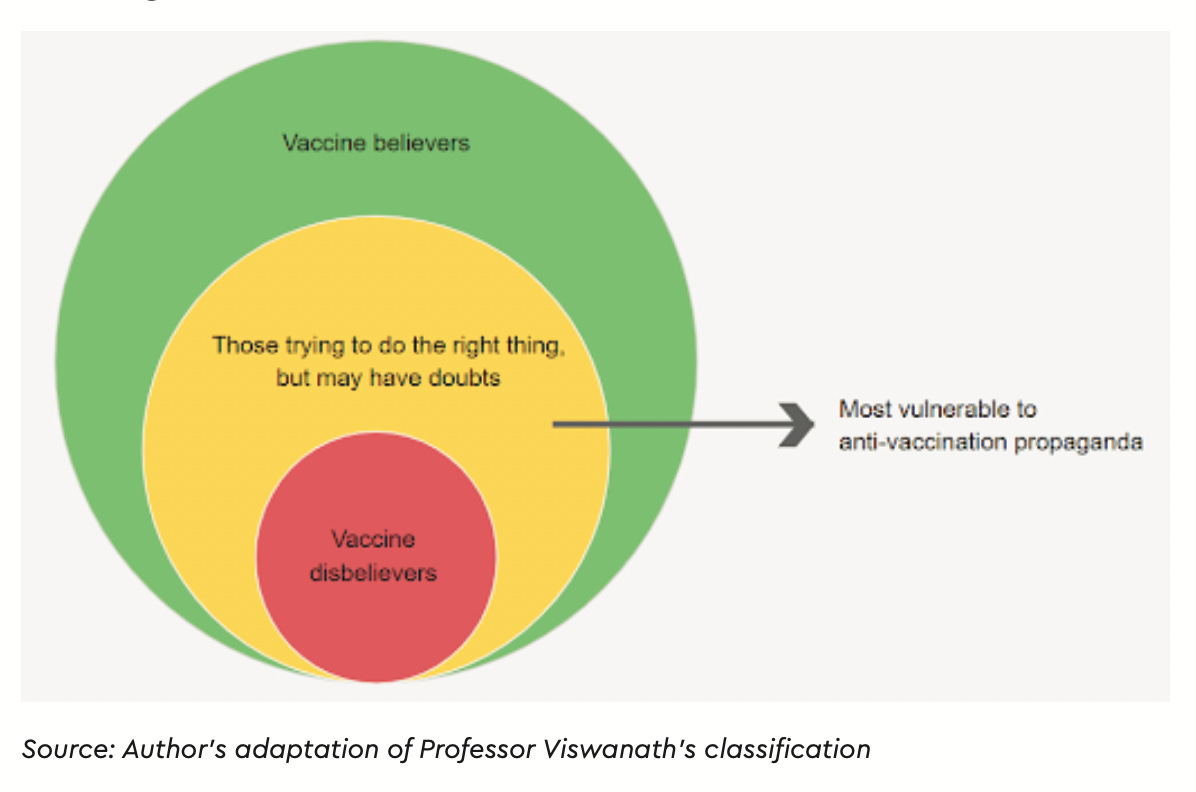

Even public health specialists have ranked the faiths! Professor Kasisomayajula Viswanath, Lee Kum Kee Professor of Health Communication at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, sees anti-disinformation campaigns being most effective for those somewhere in the wishy-washy middle between belief in vaccines and belief against them. Those most likely to be converted, redeemed, saved, from brainwashing.

And it’s this redemptive fetish that keeps Covid-related communications in the U.S. both one-note and self-defeating. Vaccine disinformation and disbelief, while very important, become the issue, ostensibly curable with a better algorithm. Government practices like vaccine nationalism are rendered moot, profit-driven reopening plans irrelevant, even as continued vaccine hoarding and “post-pandemic” farces help more variants emerge and spread. Tree and forest alike involve technology: pharmaceutical manufacturing and distribution entail decidedly mechanized processes, but require a more diachronic reckoning with capitalism (rather than supposedly “new” Big Tech) to confront. Nature isn’t healing and neither are we :/

Divine Innovation is a somewhat cheeky newsletter on spirituality and technology. Published once every three weeks, it’s written by Adam Willems and edited by Vanessa Rae Haughton. Find the full archive here.

I love reading your stuff.

However, like many others, you include links that can't be read without a subscription to whatever is at the other end! I have to believe this isn't nefarious, you aren't getting paid for these links. You no doubt check and seem to have read the articles being linked to.

I find it frustrating. I can't afford subscriptions to 100 publications!